I'm Too Risk-Averse for Index Investing

Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Stock Market

The Russian stock market collapsed about three weeks ago. Technically it still hasn’t opened yet, but the value of Russian shares in London and New York exchanges disintegrated overnight.

The Wall Street Journal reported that:

Exchange-traded funds specializing in Russian stocks are down 90% or more from their highs shortly before the invasion of Ukraine—but, as of Friday, most of them are also frozen.

The Russian stock market may eventually recover - though it might be decades from now. If ever.

This is actually not as uncommon as you might think. And it doesn’t take a war for a stock market to crash and stagnate for decades. I’m probably more risk-adverse than most, but this highlights for me the anxiety I’ve had about the risks of passively investing in the stock market.

Risks to the Index

I’ve heard the argument that on average the stock market returns ~7% a year, and if you stay in the market index long enough it’s very low risk. I think that is simply fundamentally wrong.

Yes, if you look at the American stock market over the last one hundred years or so (during the American Centry) the market has indeed recovered from all of its crashes and returned a healthy profit.

I don’t believe that time frame is long enough that we can comfortably extrapolate this performance. Moreover, I think it’s a narrow-focused look at one country that presumes that the future will look like the past without explaining the mechanism behind these continued returns.

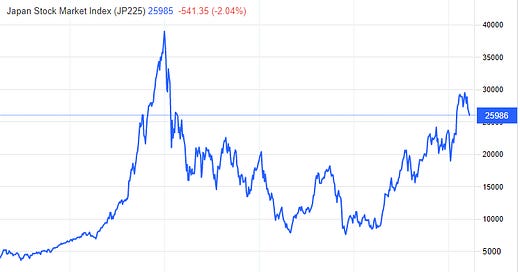

Look at Japan - had a bubble in 1990, still hasn’t recovered 30+ years later.

Japan is far from the only example.

France is flat for the last 22 years. Greece - way down. Spain, Italy. I could go on for some time. Shanghai, Australia, Saudia Arabia, etc.

Take a look at some of the stock markets around the world. Some of them have been going up with no end in sight. But a lot of them have stagnated. A lot of these countries at some point had a stock market bubble where valuations soared to unreasonable levels, and they’ve never recovered from the fall of that business cycle.

Given the current situation here in the U.S., that should give people who are passively investing in an index reason to pause.

Valuations

Consider two of the most respected indicators of a stock market bubble:

There’s the Buffett Indicator (Market Cap to GDP ratio)

and The CAPE ratio:

Just glancing at those graphs shows we could be in a bubble. Am I proposing that you should try to time the market? Absolutely not. The market could easily continue like this for decades. And if you did pull out before the crash - how would you know when to get back in? I’m just highlighting the risk to the index - I don’t believe it’s the low-risk investment that it is sometimes portrayed to be.

Yes, in some ways you reduce risk by buying an entire index - you’re insulated from things like an accounting scandal or localized problems. But you open yourself up to different systemic risks. The index could - as we’ve seen in many countries - crash and never recover, or just have decades and decades of slow decline.

Demographics

I also want to highlight the demographic side of things. This is one of my favorite graphs. Look at the rise and fall of the world’s population growth rate. It’s really unprecedented in all of human history.

The reason the graph looks like this is because fertility rates bounced up (the baby boom) and fell off a cliff (well below the population replacement rate) shortly after.

So, while the total population will continue to grow for some decades- the working-age population has already begun to shrink.

My point here is only that I don’t think it’s reasonable to extrapolate past performance into a very different looking future. Since the collapse in fertility rates, the world has benefited from the demographic dividend of reduced dependency ratios - a trend that will sharpy reverse when the baby boomers retire. (Charles Goodhart has done excellent work on the economic impact of changing demographics if you find the topic interesting).

The Alternative

Maybe you can agree that the risks to passive index investing are underappreciated - but what’s the alternative? We can’t time the market and 89% of professional active hedge fund managers can’t beat the market.

That is true.

And it seemingly leaves us with few options. With inflation as high as it is, you can’t even hide your money under the mattress anymore. So where is someone as risk-adverse as myself supposed to put their money?

Value Investing

While it’s true that most hedge fund managers don’t beat the market, there is one kind of investor who has. Warren Buffett made the argument for it in his classic essay The Superinvestors of Graham-and-Doddsville. Where he points out the statistically improbable number of value-investing adherents who consistently beat the market.

The idea of value investing is simple:

The value of a business (or at least some businesses) can be roughly calculated +/- some margin of error.

The stock market is sufficiently irrational that in the short-term prices vary significantly at times from this intrinsic value of a business.

The long-term price of a business tends to match its intrinsic value.

Or, as the father of value investing Bengamin Grahm put it - "In the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.”

Now valuing a business precisely is impossible without perfect future knowledge - but there are some businesses where you can come up with a rough value. To quote Warren Buffett again on the process of valuing a stock:

…make a very general estimate about the value of the underlying businesses. But you do not cut it close. That is what Ben Graham meant by having a margin of safety. You don't try and buy businesses worth $83 million for $80 million. You leave yourself an enormous margin. When you build a bridge, you insist it can carry 30,000 pounds, but you only drive 10,000 pound trucks across it. And that same principle works in investing.

This takes us to the second point - is the stock market sufficiently irrational that in the short-run prices vary significantly from a calculatable intrinsic value of a business? This was the hardest part of the value-investing concept for me. There’s a part of my brain that can’t get over the idea that markets are pretty efficient. Thus, how could there really be money “laying around.” And if there were, I thought - value investors would have a huge incentive to buy these undervalued stocks and remove the gap. But again, Buffett addresses this point - and points out that in fact value investors have been consistently beating the market. He says:

I'm convinced that there is much inefficiency in the market. These Graham-and-Doddsville investors have successfully exploited gaps between price and value. When the price of a stock can be influenced by a "herd" on Wall Street with prices set at the margin by the most emotional person, or the greediest person, or the most depressed person, it is hard to argue that the market always prices rationally. In fact, market prices are frequently nonsensical.

he goes on to give an example:

One quick example: The Washington Post Company in 1973 was selling for $80 million in the market. At the time, that day, you could have sold the assets to any one of ten buyers for not less than $400 million, probably appreciably more. The company owned the Post, Newsweek, plus several television stations in major markets. Those same properties are worth $2 billion now, so the person who would have paid $400 million would not have been crazy.

If you find this idea of market inefficiency hard to believe, consider this - we have all seen stocks that are irrationally overpriced. Look at all the meme stocks. I can tell you with great confidence that investors in AMC will not make a good return should they hold over the long-term. In the same way, at times the market will irrationally undervalue stocks.

But let’s not just take Warren Buffett’s word for it.

In 1992, data compiled by Nobel laureate Eugene Fama and Dartmouth professor Kenneth French:

…rigorously demonstrated that value stocks, especially small-value stocks, had a statistically significant edge over growth stocks and the market as a whole. [emphasis added]

To be fair, when they revisited their work in 2019 they found that the value premium had shrunk. Although the greater volatility of recent decades meant that they were unable to say with statistical significance that the value premium was not as large as it had been found to be in the past.

Fama and French found that, during the earlier time period, the value premium was a more consistent, moderately positive number, allowing them to estimate it with statistical confidence. In recent years, however, greater volatility of value-stock returns widened the range of plausible premiums—including, for the first time, negative estimates—and blurred the picture. “The declines from 1963–91 to 1991–2019 in average premiums for the value portfolios seem large, but statistically they are indistinguishable from zero,” they write. In particular, they are unable to reject both that the value premium is still as large as it has been historically and that the value premium has been zero in recent years.

However, there is a huge flaw in this research. And really just about any similar analysis that tries to compare Value Stocks vs Growth Stocks or the market index. The only way to determine which stock are “value stocks” in such large decade-long study of the entire market is to look at ratios like the book-to-price ratio (A ratio of the value of the assets a company holds to its market price) or the price-to-earnings (the ratio of its market price to earnings per share). But while those are important metrics (though substantially less so in today’s world where a greater and greater amount of value comes from intangible assets). Good metrics alone do not make a stock undervalued.

For a quick example, take a valuation I just made of Smith and Wesson Brands Inc (SWBI). The ratios for it are fantastic. If I was making a study of value stocks based on ratios this would have to be included. But here’s the thing - look at the stock for ten minutes and it’s easy to see why the ratios look so good. Look at their YoY quarterly growth.

It’s a very cyclical stock. It roughly follows the political cycle as politics (and apparently pandemics) make people buy more guns. Despite some of the best metrics around, a Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Valuation with some reasonable assumptions about future growth, and taking into account the cyclical nature of sales, shows it to be ~11% overvalued.

Another example would be stocks associated with shopping malls. As the future of malls looks fairly bleak, they are trading at a low multiple of their earnings. But again good ratios don’t make necessarily make a value stock. The point I want to make here is that you can’t just looks at the metrics which are based on the last 12 months and call something a value stock. If you do, you will include a lot of stocks whose metrics look cheap just because the market realizes that there’s a reason that the future won’t be like the recent past. Cyclical stocks will have the best metrics just before they crash and so would companies who’s futures look bleak.

Honestly, I think it is telling that from the 1930s to the 2000s such a simple metric that is only loosely connected to the actual intrinsic value would beat the market.

Summary

In summary, what I’m arguing is that the risks to buying an entire index are underappreciated, and that is possible to look at the financials of a company and see if they’re reasonably priced. I personally sleep better with a portfolio of companies that I think are intrinsically worth what I paid for them.

If you want to learn more about Value Investing, here are some beginner books that I found helpful to learn more about investing / value investing:

The Little Book That Still Beats the Market

Why Stocks Go Up and Down (not a value investing book, but as it says “The book you need to understand other investing books”)

Probably the best possible source for the mechanics of how to value stocks is NYU Professor Aswath Damodaran. And a fantastic resource is tracktak.com a webapp based on Damodaran’s spreadsheets.

All content is for discussion, entertainment, and illustrative purposes only and should not be construed as professional financial advice, solicitation, or recommendation to buy or sell any securities, notwithstanding anything stated.

There are risks associated with investing in securities. Loss of principal is possible. Some high-risk investments may use leverage, which could accentuate losses. Foreign investing involves special risks, including a greater volatility and political, economic and currency risks and differences in accounting methods. Past performance is not a predictor of future investment performance.

Should you need such advice, consult a licensed financial advisor, legal advisor, or tax advisor.

All views expressed are personal opinion and are subject to change without responsibility to update views. No guarantee is given regarding the accuracy of information on this post

I stopped reading when you didn't consider dividend for Japan's index.

If you had DCA'd into the Japanese market you would still have made money. So perhaps the argument is that lump sum investing is too risky? Even though studies show it outperforms compared to DCA that is only true when the market is continually going up (which most of the time it does) but if you're somewhere where it does not do that like Japan then there is an edge of DCAing over lump sum.

Curious to hear your thoughts.